If you develop software, a fork isn’t just a utensil. It indicates a divergence in a codebase. Code gets forked for several reasons, different opinions, access rights, making a pull request into the upstream repository, etc. There is the correct way to fork software. Then there’s what I call a naked fork. A naked fork is summarized below.

git clone [git@github.com](mailto:git@github.com):someone/something.git cd something rm -rf .git git init git add * git commit . “First commit, forked from something” git remote set-url origin [git@github.com](mailto:git@github.com):me/something.git git push

If you don’t understand what’s happening here, I’ll explain. You start by cloning someone else codebase. Then nuke all the history by deleting the .git folder, creating another git repository, and then pushing it to your empty repository. You will have one initial commit in the repository, which contains the entire old repository, which could be millions of lines of code.

Let me explain why this is a terrible thing to do.

I’m working on a single board computer project similar to the RaspberryPi. However, mine is much less well known. I’m using a Lindenis V5, which boasts an Allwinner V5: a quad-core 1.5Ghz processor that you can buy in bulk for less than 10$. For those that don’t know about getting a microprocessor to boot an OS, there are three required components: userspace, kernel and bootloader. The userspace consists of all the applications you need to interact with the system, commands like ls, bash and cd. The bootloader initializes some hardware: the ram, EMMC and power supplies. It then gets things ready for the kernel. The kernel then boots as the interface layer between the hardware and userspace. The vendor has provided some support, an image containing an old Debian fork using a 4.4 kernel and a uboot repo from 2014 that doesn’t build and the source for the image.

The vendor-provided image is too old for what I’m working on, so I need to build my own image. I’m trying to determine when the vendor forked uboot, understand their diff from the mainline and integrate those into a newer version of uboot and upstream it. However, since it’s a naked fork, I have no clue where the actual fork point is. I checked the git logs, but the code is way older than the commit times are indicating, which means this is what the vendor did.

git clone [git@github.com](mailto:git@github.com):someone/something.git cd something rm -rf .git # Spend two years making your changes. git init git add * git commit . “First commit, forked from something” git remote set-url origin [git@github.com](mailto:git@github.com):me/something.git git push

I need to correlate two git repositories which are essentially time-series databases. The command required to diff two folders and count the different lines looks like this.

diff -rN -x .git ~/path/to/repo1 ~/path/to/repo2 | wc -l

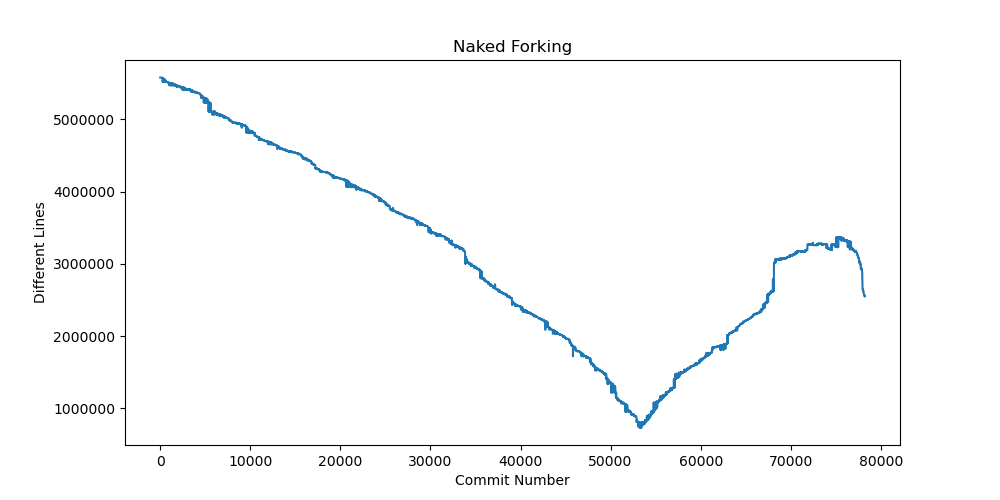

To determine the ancestry, checkout the head of the original repository, run this command, decrement one commit, rerun it, and repeat. After running this loop for three days, you get something like this.

The global minima indicate the most similar repositories, so that’s where the fork happened. I checked out this point and went from there.

Incompetency isn’t the only plot going on here. Chip manufacturers don’t seem to understand that these open-source tools are what breathe life into their products. Vendors should work with the open source community, not expecting volunteers to support their hardware by reverse engineering RAM initialization binaries (store for another time). Sometimes your average Joe can’t get a datasheet, which isn’t how things should work.

We should all strive to build software that enables hardware to do amazing things and remember: shit happens when you fork naked.